The Internet as we know it has a parasite SUCKING and SLURPING its life away, preparing to FEAST on the husk once there's nothing left to take. I call this parasite "the state," though some also refer to it as "the government," and side-effects include censorship, control, and conspiration. This diagnosis isn't mine alone, either: Many tech-minded individuals have COME or are COMING to a similar conclusion as said symptoms worsen day-by-day. But don't fret, precious, for the cure is nigh, and it'll likely be here sooner than you expect. Here's why.

What the hell is a "Renet"?

Alright, now that I have my hook I can talk like a "normal" person instead of an insane politician: The basis of the Renet theory is that the free Internet and the state are fundamentally incompatible, which is the core reason why the Internet is in the increasingly sorry state we see today, but I predict that a webvolution will arise to make the Internet ungovernable. If all that flew over your head, allow me to rephrase this thesis statement in a way most easily quoted and spread:

The Renet theory holds that interventionism is killing the free Internet, and predicts that we will eventually see a rebirth of the Internet rise to save it, likely in the form of a structural overhaul.

Now before I can say anything else, I should preface with a few things. First: I'm not attempting to be – nor claiming to be – unbiased or academical in any way here, and I will be serving my opinions cold and raw; however, by that same decision I also don't have to speak in the spiritless, supposedly "professional" tone that I despise, so expect this writing to have something resembling life in it; lastly, try not to take me too seriously because nothing really matters and I may be "under the influence." Consider this whole thing a informal-formal polemic proposition of my socio-politio-techno theory… if you're still here after that, then enjoy your reading.

First: What is a state, and why is it bad for the Internet?

If you're not sure on what a state is, or even worse, you think it's just one of 50 units of land that makes up a certain country, let me try to define it in a way any layman can understand: A state is an entity within a society that claims to hold a monopoly over the use and justification of force. The reason why you typically hear "government" and "state" used interchangeably is because the "government" is the operational arm of the state – the parts you probably envision when you hear either term, like the military, police, courts, etc.

With this definition in mind, it's not hard to see why the state and the Internet would conflict: They're fundamentally incompatible. The Internet is a decentralized information-sharing network, making it simple for anyone to run a service for any purpose, illicit or otherwise – no prior authorization necessary. The state relies on its ability to enforce its force-monopoly to function, which is very challenging without centralization and compliance. And you can see this contradiction play out constantly, if you're aware of it, such as the ultimately lost war against The Pirate Bay, the borderline malicious persecution of Ross Ulbricht over the Silk Road marketplace, and much more I'd like to rant about here, but shan't. Stories for another blog post.

But let’s tackle the most obvious objection up front: “Wasn’t the Internet itself born from the U.S. government? Were they a bad parent even then?” And my answer to that is "Yes, I believe so."

While it is true that the U.S. government planted the seeds of the modern Internet, they also raised those seeds in a bunker 6.21 miles (or 10km) beneath the Earth's surface. ARPANET, the Internet’s ancestor, was a Cold War research project bankrolled by DARPA. Its purpose wasn’t to connect the commoners, it was redundancy for generals — a communications network hardened against nuclear attack. The decree of that design brief poisoned everything else that followed. Packet switching, TCP/IP, the “digital handshake” — all brilliant breakthroughs, but all engineered for resilience and identification inside a closed military-academic system, not for privacy or autonomy. That’s why today, half a century later, you’re probably tunneling your traffic through a VPN so your ISP won't see you reading this crazy guy's ramblings.

And that origin matters. How does the state get the resources necessary to fund a multimillion dollar experiment like this? I'm sure you already know: Taxes. And they will always get their tax money – after all, it's within their monopoly powers to demand it. So even if ARPANET ended up being a massive waste, what does the state care? They're effectively gambling with somebody else's money. Of course, in this case they happened to have won, but the point of my rambling is that their inefficiency and self-interest is always going to be present in the modern Internet's "DNA," to some extent, thanks to ARPANET. And although it's hard to imagine, the principle I just described backs my assertion that the Internet would've been better off had it been in the exclusive custody of the private sector from the start. In other words: I believe we could've already been at the Renet by now if corporations had developed the prototype instead.

If you're not yet convinced of the government's detrimental influence, let me rattle off a few quick examples. NSFNET, the federally funded backbone of the early Internet, explicitly banned commercial traffic until 1991, strangling early entrepreneurial experiments in their crib for no defensible reason – because I'm not convinced that nobody would've bought a football mug at a blazing fast 1.5mb/s (max) text-only in the '80s. *gasp* And through the ’90s, strong encryption was classified as a weapon and restricted on that basis ("WE are the only ones allowed to have weapons!"), forcing browsers to ship with laughable “export-grade” SSL. If that's all not enough: The U.S. government also held a de facto monopoly over the .com, .net, and .org domain names through an exclusive contract given to Network Solutions for years, meaning you couldn't get a "trustworthy" domain name without passing through the government's digital proxy toll booth. All of these issues may be insignificant individually, but all-together they paint a clear picture: The Internet's growth, stunted by a paranoid parent, terrified its rebellious child may grow up and move on.

And I'm not done yet. Though I'm fairly confident in my assertion that state interference was always an issue, and still is, the state's meddling in the modern Internet may be less obvious. For this, I'll use but one powerful example to show that things have arguably only gotten worse: Yahoo v. The United States (Government) (2008).

In 2008, when the Bush administration demanded user data en masse under the FISA Amendments Act, Yahoo resisted, for both its own interests and the interests of their users, asserting that the demands were "unconstitutional and overbroad." Despite risking $250,000 per day in fines, doubling each week, they fought back in every court they could… and they lost. Not because they were wrong, or because of a flaw in some system, but because the systems were working exactly as they're supposed to: To protect and serve the state's interests, with those interests being to maintain its monopoly on the use of force (i.e., not because every Yahoo user is a confirmed terrorist). And as an additional slap in the face: Yahoo was forbidden from speaking of this case (which has immense legal precedence!) for years, until documents unsealed in 2014 made the situation public. And even then, the documents were never fully declassified, because "national security concerns."

And judging by PRISM's existence, Yahoo was probably just the loudest casualty, but further examples aren't necessary anyway because the point's been made crystal clear: If the state wants your data, you will hand it over or die resisting. That’s the environment we live in now. And while it's true that companies have plenty incentive to data-farm their users – namely analytics and personalized advertising – in a truly free market, privacy itself would be a competitive edge, much more than it is now. Chrome would look a lot more like Brave Browser, Gmail like Proton Mail, because smart users want it, and companies want to convince smart users, because dumb users will just use either whatever's default or whatever was popular amongst the smart anyway. But the threat of the state warped those incentives: It taught every tech giant that resisting is suicide, that compliance is mandatory, that surveillance is not just situationally profitable but expected. The modern “surveillance economy” didn’t spring from some greedy capitalist twirling his mustache in Silicon Valley and going "Neh-heh-heh-hehhh!" – it metastasized because governments normalized this betrayal until every user was a statistic. Quick aside: But this is why adding Google Analytics to your website makes you part of the problem, and why you should stop that.

Actually, "normalized" may be an understatement. The 2022 release of the "Twitter Files" shows just how casual the connection between social media companies and the federal government has become. The documents reveal evidence of multiple political parties and federal agencies controlling the narrative by gagging certain accounts, posts, and even news, such as the Hunter Biden laptop story, across multiple social media services, not just Twitter. My favorite image to come out of the dump shows an exchange between two Twitter employees; the first message is just a raw list of tweets to censor forwarded from "the Biden team," and the reply is just "handled these." Poetry.

I could go on and on with more examples forever – maybe touch on the whole TikTok/CCP (Chinese Communist Party) situation, for instance… but I don't need to. At this point, a pattern's been firmly established: Since the dawning of our great interconnected-computer network with ARPANET all the way to today, state intervention on the Internet has always been to the detriment of the common user, at least eventually. Sure, perhaps somebody is benefiting, but that somebody is not me, and it probably isn't you either, unless you're the token fed assigned to my case. The state's duty to those who empower it ends the minute the state can justify violating their rights as "protection," and the modern Internet is a perfect example of this protectionist paradox™ in-action.

Is this what you want?

No, I'd say you probably don't want bureaucrats and faceless agencies dictating what you get to say and do online, because almost nobody does. People tolerate it because they either assume there's no alternative, or they don't recognize the heart of the issue in the first place – the state v. free Internet conflict. But how do we actually resolve this conflict? I see only three options: One naive and temporary, one a little too revolutionary, and one a practical solution.

Option 1: Make the Internet Great Again

The first answer is to "just say no" to state intervention. The public demands that the government be limited back to only what's necessary to protect the populace, something like "no sensitive user data except by court order, no restricting freedom of expression, no unconstitutional extortion of corporations, etc." Are you getting déjà vu? That's because this is exactly where we were in 2008, and I don't think I have to remind you how that turned out for Yahoo. One more time for absolute clarity: History's shown that "just saying no" to the state doesn't work, since their vague interpretation of what constitutes a "national security threat" effectively overrules your rights when they dictate what constitutes a right anyway. And the notion that we should try again because "maybe it will work this time!" is blind nostalgia at best, and complete insanity at worst.

Option 2: Nuke the State (METAPHORICALLY!)

Second answer's the most radical: abolish the state outright. No state means no perversion of netizen rights, no perversion means… well, I fucked that rhetorical tool up, but you get the picture. This is the solution that I believe would produce the best results for society as a whole. The problem is that it's extremely unlikely that we'd get everybody to agree to abolish the state within the next century, considering there's no examples today of a totally free society to point to, and many have been preconditioned to believe that it's a necessary component of a society due to sheer prevalence. So objectively correct or otherwise, we're probably not going to Ancapistan anytime soon – unless somebody starts dumping gold-and-black pills into the water.

Option 3: Build a Better Internet

Finally we arrive to the most practical answer: Make the Internet itself ungovernable, i.e. reconstruct the Internet's architecture in a way that makes censorship perhaps not impossible, but economically or technically infeasible. That means replacing HTTP(S) – the protocol that glues the modern web together – with something designed from the ground up to be hostile to anyone who tries to domesticate it, or especially neuter it.

And I can already hear some of you nerds adjusting your glasses: “Uhh, ever heard of Tor? IPFS? Hyphanet?” Yes, I have. They’re all technically impressive, but using them feels like being a mountain man in the digital Appalachians – resilient, resourceful, perhaps even wise, but not exactly viable for everyone. None of these protocols are useless; in fact, each one solves a piece of the puzzle. Tor’s "onion network" isn’t flawless, but it’s the most successful “deepnet” today, keeping countless whistleblowers and dissidents alive. IPFS’s distributed storage is promising, though the jury's still out on its ability to actually protect user's security or privacy. And Hyphanet’s configurable security philosophy is very appealing to power users, but perhaps only power users.

Point being: A hypothetical “Renet protocol” need not reimagine the wheel from a void – it could just as easily evolve from one of these examples. But regardless of what path it threads, this protocol would have to be definitively superior to HTTP, not just situationally superior. You can’t just duct-tape a blockchain to a mesh network and call it a day. HTTP dominates for a reason – it’s flexible, scalable, and battle-tested, much like duct tape – used for keeping a victim's mouth shut (too hyperbolic?). For a Renet to win, it has to commandeer the hearts and minds against the Leviathan. To stick with the mountain metaphors: that’s like trying to mount Everest. Ample as her curves may be, we must not forget the crazy-hot matrix, in our assent towards uhh… Anyway, the point here is: I’m not a computer science major, so I wouldn’t know how to summit Everest myself. But I do know one fundamental rule of economics: Where there’s demand, there’ll eventually be supply. And judging by how every tech enthusiast describes the modern Internet like it’s a post-thermonuclear war-crime scene, I’d say demand’s doing just fine.

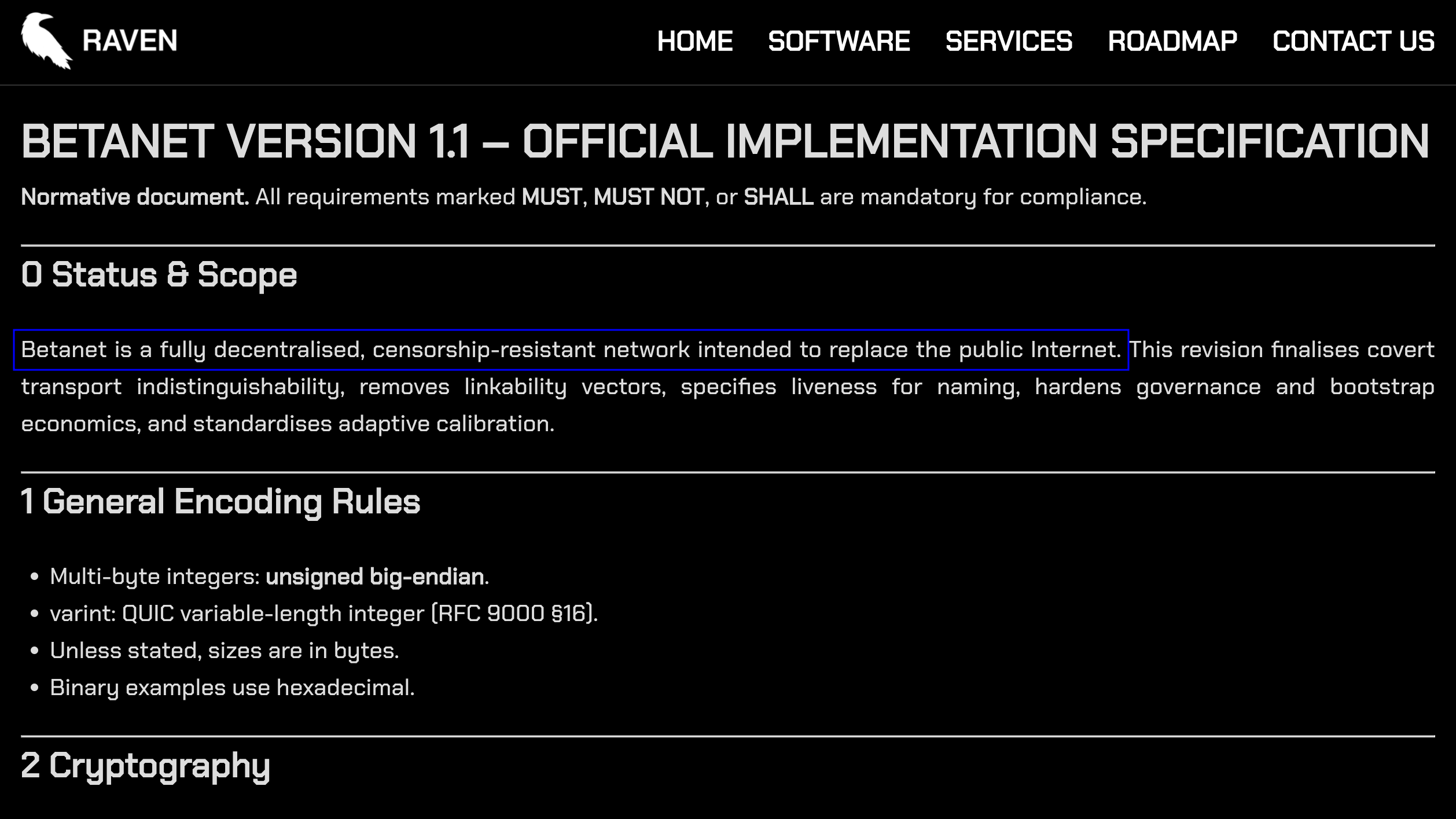

Case in point: Betanet. Funnily enough, I didn’t even know it existed when I started developing this theory – I only found out that some lunatics were taking a modern crack (poor choice of words but I'll keep it) at what I've been day-dreaming about when I heard that their own web host shut them down without warning and held their files hostage through the You-Tubes. Is this whole situation just pure comical coincidence? I think not.

Now let me be clear: I’m not saying Betanet is destined to be the Renet. Hell, it may very well be dead by the time you’re reading this. I bring it up because its mere existence, and the skirmish with its hosting provider, proves my point perfectly: the demand is real, the willpower is real, and most interestingly, somebody seems to view it as a real threat. Maybe the mythical "Renet protocol" won't be Betanet, maybe the real Renet won't arrive for many years, but you shouldn't dismiss the vision of an Internet rebirth, especially considering the conflict that's hopefully been made crystal clear by now. History is full of failed prototypes – but equally full of revolutions built off their backs. It's important to remember that evolution takes time.

Finally: Will the Renet become Web 3.0?

…And it really is evolution, isn't it? The Internet may not be a sentient being (I hope), but it evolves much in the same manner as one, just significantly faster due to not being constricted to one form like we are. The Internet's only getting more and more strange – That is to say that by its nature it defies consistency and familiarity, because every 'site and every user you see today is a mere ephemeral presence in the greater 'net. Every website you know will eventually go offline, at least in its original form, including every site I've linked to in this post and the post itself; the lucky ones leaving behind echoes in the form of mirrors and mentions.

You may have noticed my usage of the term “netizen” a few times. What does it mean? Honestly, I'm not sure; I think I saw it in Cyberia and thought it was cool slang (Great book; I'd recommend it to readers still with me here). But in writing this blog post, I think I've come to actually understand what it means: A 'netizen' is anyone who accepts the Internet for its fleeting, ever-mutating nature, and chooses to participate anyway. Doesn’t matter whether you’re running your own server in a basement or just shitposting from a rented corner of Zuckerberg’s walled garden – if you understand, then consider yourself a child of the machine. The only real difference is that webmasters leave better fossils…

What the fuck am I talking about again? Oh right: If there's one thing you should take away from this Internet history lesson, it's that the state ruins everything. Second to that is that a free Internet has the potential to be a powerful force for good. A human alone can survive, but if you have many like-minded men working together, you have a society that's beneficial to all involved. A computer too is great alone, but nobody today buys one without the intention of connecting it to the Internet, unless they're planning to mail a pipe-bomb or something. The free flow of information through these networks has the potential to bring us unfathomable prosperity – even more than it already has – provided that we allow it to. Hearing this: Why wouldn't you support a Reborn Internet?

Of course, the Renet won't be perfect. The Internet can never be censorship proof as long as there's still a state capable of censoring it. For instance: Public figures have an unfortunately difficult time staying anonymous. I personally try my best, but I know that as long as I choose to operate under a single unified identity (Crigence), no degree of OPSEC is going to stop a dedicated force from data-scraping together a psychological profile on me. This would be a good example of what I call 'the scalability paradox', which I'd define as the assertion that decentralization may be more robust and resilient, but ultimately centralization is necessary for efficiency and growth. This manifests in many ways, not just having to centralize your identity to become recognized; I'll cite YouTube replacing the need for sites to host their own videos as a quick and easy example. So a hypothetical Renet can never be "censorship proof" because it will have to centralize in one way or another, and then you reintroduce the opportunity for censorship. In other words: Fighting for digital freedom against the Leviathon is always going to be akin to playing whack-a-mole with a hydra on bath salts.

So why am I out here pitching a flawed theory? Because I can. This is my blog, I get to rant about benign bullshit, and somebody will read it anyway because I'm a good writer. Yes, a writer who loves to stroke his ego, not too many of those I'm sure. Besides, if it was The Renet FACT, I wouldn't be calling it a fucking theory, now would I? Serious question, I don't know – This is some damn good stuff. "Stuff" of course referring to legal medicinal cannabis for my medically diagnosed ADD (I swear officer). But regardless of whether I am or am not tripping, I think one thing's for certain: "The Renet Theory" is inspiring, and very marketable.

And uhh, yeah, I guess that's all I've got. Thank you for your interest in my theory, if indeed anyone is. I spent a while developing it, and a while realizing how it's beautiful and how it's flawed, and I now feel confident unleashing it unto the Wire and letting it go where it may. I'd say that if I managed to bring even one of you into my strange psychedelic vision of the future Internet, I'll know I have succeeded. On that note, help yourself to the highly shareable goodies at the bottom of this blog post. Good night, netizens. – Crigence

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)